Horrific Performance

An initial investment of more than $450,000 to the ProShares Ultra VIX Short-Term Futures ETN (UVXY) at the open of its October 4th, 2011 inception date (the split adjusted opening price) would be worth just $87 at today's close (this after a more than 28% gain today and more than 300% gain over the past few weeks). Modeling what the performance would have been going back to the inception of VIX futures in March 2004, a $100 million initial investment would be worth a bit less than $5 today (you read that correctly).

Investors Haven't Fared Better

Given the above performance figures, it should be no surprise that UVXY has eaten a tremendous amount of the capital investors have sunk into it. Since its launch, the ETN has seen net flows in excess of $1.7 billion, while current AUM stood at less than $400 million as of yesterday's close (simple math tells you investors have lost more than $1.3 billion in the strategy since inception). This figure may improve short-term, but I all-but-guarantee it will get worse over the longer term.

As an aside... how in the world is UVXY accessible by mom and pop investors who have zero clue how it works.

What is It / Explaining the Underperformance

The ETNs description:

The Ultra Fund seeks daily results that match (before fees and expenses) two times (2x) the daily performance of the S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures Index. The index seeks to offer exposure to market volatility through publicly traded futures markets and is designed to measure the return from a rolling long position in the first and second month VIX futures contracts.

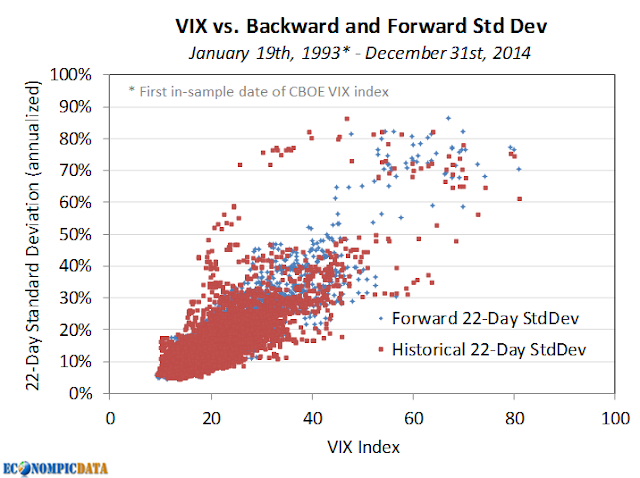

To summarize, the ETN provides exposure to a long position in the front two VIX futures contracts at 200% notional (i.e. it is a 2x levered position). If VIX futures simply followed the VIX, UVXY returns would be extremely mean-reverting as the VIX is one of them most mean-reverting figures in all of finance as it cannot go to zero or infinity. But, while VIX futures do typically move in sync with the VIX index over very short periods (i.e. the exposure most investors in UVXY believe they are getting), it does not over long periods of time.

The issue with VIX futures is the term structure, which during calm markets is typically in

contango (i.e. VIX futures are priced higher than spot), while during distressed markets is typically in

backwardation (i.e. VIX futures are priced lower than spot). UVXY benefits immensely from backwardation because the upward slope of VIX futures owned provides a tailwind to the futures contracts as they approach maturity (while UVXY faces a severe headwind during contango... which is present much more often).

Examples of VIX futures in contango (bad for UVXY) and backwardation (good for UVXY) is shown in the two below charts using data / charting from the especially helpful

VIX Central (follow

Eli on Twitter).

Example of VIX in Contango (6/23/15)

Example of VIX in Backwardation (9/1/15)

Using UVXY

All that said, there is absolutely a case for going long VIX futures / VIX ETNs. As the last few weeks have shown, there are very few financial instruments that have a correlation near -1.0 to stocks during periods of market distress.

One way to make an allocation is to simply allocate to a long VIX futures position only when they have a tailwind vs. headwind. Simply calculate the term premium (a simple way is to use the VIX/VXV ratio - details of what that is by the great Bill Luby

here) to determine contango or backwardation (in this case when the VIX/VXV is less than or greater than 100) and only allocate to UVXY when it's above 100. To put some numbers behind that statement, the average modeled daily performance of UVXY is -1.1% when the ratio is < 100 (2500 trading days) and 5.0% when the ratio > 100 (378 trading days) since 2004.

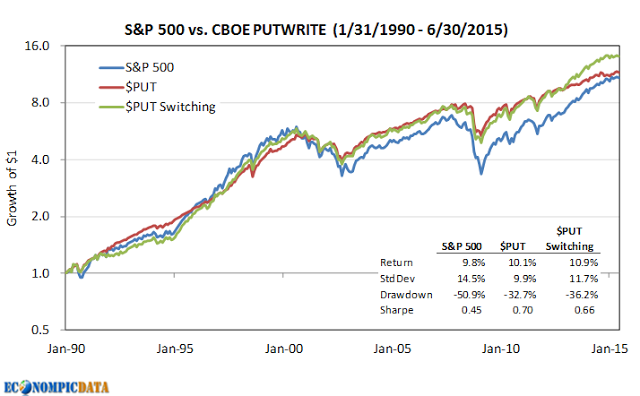

As an example of putting this to work within a portfolio, below is an allocation to the S&P 500 compared against an allocation to the S&P 500 when the term structure is in contango (bad for UVXY), or a 83% allocation to the S&P 500 / 17% allocation to UVXY (UVXY is ~5-6x more volatile than the S&P 500 over the long-term) when the term structure is in backwardation (i.e. favorable to UVXY).

The above breaks down to annualized returns of 6.9% for the S&P 500 and 12.4% for the hedged version, while standard deviation moves from 19.6% for the S&P 500 down to 15.5% for the hedged version. In addition, max drawdowns moves from 55% down to 29%.

So, while I certainly feel the average retail investor should

not be allowed access to something as volatile as UVXY without proof they have a good understanding of the mechanics that drive performance, I do think there is a benefit in using such vehicles for those that understand how they might tame them.